Never Settling

By Marin Warshay

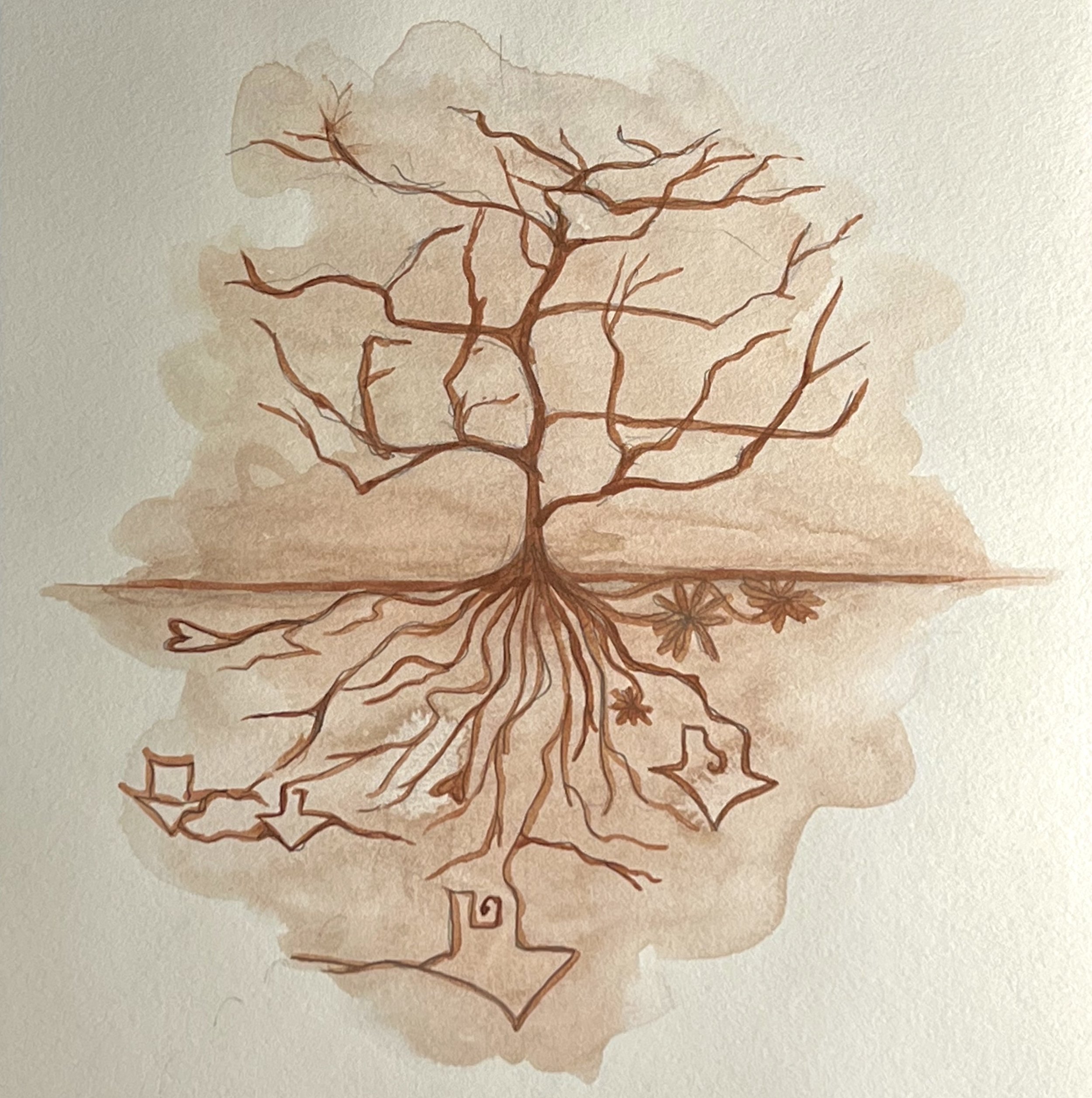

Illustration by Ana Vissicchio

“If you could only bring one thing to a deserted island, what would it be?”

Remember that game we used to play?

Don’t deny that you used to run an escape plan through your mind for the inevitable moment that you’d be confronted with a puddle of quicksand. Or a falling glacier. Or a tsunami that you saw on TV in that one movie. What was that about?

For a while I used to laugh at my younger self for engaging in such “impossible scenarios.” But they don’t seem so far-fetched anymore. Is it possible those hypotheticals were in preparation for something? Maybe it was our brains’ way of foreshadowing. Maybe it was our way of coping.

The temporality of climate change is all around us.

I recently spoke with Jon Robertson, a survivor of the 2017 Thomas Wildfire that ate through Santa Barbara, California and surrounding areas.

In 2017, the Robertsons played that game. Their life was deserted. But instead of sand, ash. Upon learning about the logistics of having to promptly decide what was most important of all of his belongings, evacuate his home, and search for new shelter, I noticed a specific thread that stitched through his entire recount.

He told me about his daughter. He told me about her plan to become a professional costume designer. Once he told me about the portfolio she had been working on, hours felt like too small a unit of time to correctly valorize her efforts. Clippings of her fabric, design sketches, and complete costumes that have been worn by actors with just as big dreams as hers. Only one of many casualties in the Robertson family household; not to mention Jon’s wife’s late mother’s paintings, three wardrobes they’d spent their lives building, and an entire house that they could barely afford but were planning on retiring in. Jon, although unable to corroborate this, heard that the fire was moving one acre per second. He thinks this is why neighbors immediately next to him were left untouched. So swiftly moving that his house, and the home within, were gone as quickly as a gas stove can ignite.

Each generation can be attributed to an era of loss and struggle—anticipation of nuclear warfare, a rise in terrorist attacks, a crash of the economy, a constant flow of mass shootings, a mental health epidemic, just to name a few. But the climate crisis feels unique in that it was heavily predicted, it’s currently experienced, and its future implications are certain. It’s been here and it’s here now and it’s here to stay. Talking to my peers, it is clear that the concept of permanence is harsh waters to tread when imagining our ideal futures. Factors like rising sea levels, food shortages, our tolerance to extra high temperatures, and what kind of natural disasters we may face will certainly be factored into our decisions, if they haven't been already. Every generation has had to cope; it’s a fact of life. It’s the name of the game. But it feels like we’re the generation of pre-coping. What’s worse: knowing early that we have to make these sacrifices and fearing the forever lack of stability or having already set down roots for you and your family and having to start over?

Hearing Jon’s story, my mind went straight to “so what’s the point of settling down?” It's only a matter of time before we are all physically and spatially affected by the climate crisis. Whether that’s in the form of our home burning down, our streets flooding, breathing through masks, adjusting to staring at screens more than ever before, or eggs tripling in price again, sacrifices are already being made and the strides we make in building up our lives no longer feel permanent. It’s like we’re building a tower of rocks in descending size order only to realize the higher we go, the more precarious our structure gets. Nevermind the environmental harm of overproduction, what’s frightening is the emotional risks of working hard just to lose it all.

But when I asked Jon whether he felt hesitant to materially rebuild his life as abundantly as he had before, he said no. In fact, he felt the opposite. Once all of his, and his family’s belongings were destroyed, he decided that everything he would buy would be an updated version of what he had before. If he was gonna spend money, he wanted it to count. Being as fortunate as he was to have the means to do so, it was his way of coping. It was his way of feeling human in the midst of something that he “could barely wrap his head around.”

The phrase “new normal” jerks my body into fight or flight. It’s almost meeting the three-year mark of being sent home from Freshman Year of college due to the pandemic. How nice it feels to get further from that moment. But it seems like the new normal is something that is ever-evolving. The tippity top of a treadmill band that’s impossible to reach no matter how fast you run. It’s a concept, a mindset, that will be ingrained in young consciences. It has to be. There can simply be no more “out of sight, out of mind.” But how do you teach a child to prepare to lose what they just got? How do you teach a being, new to this Earth, with no object permanence, of a disappearing world? Like Jon said, it may have felt materialistic but the objects that we surround ourselves with are critical to building our sense of self. It’s human to collect. It’s human to settle. It’s human to lay down roots. Who will we be when our need to be grounded by physicality is constantly being put to the test?